Background

It is a natural reaction for institutions and individuals to want to find out how much money their investments have earned or lost. This need to know holds the investment community accountable and is an important requirement of successful investing.

Discovering investment gains and losses lead to actions with the expectation that gains will be repeated and losses avoided. The actions are often counterproductive, as this paper will show.

The expectation that investment returns will persist underpins many ERISA litigation cases that look at investment returns in hindsight as a sign of fiduciary breach.

Repeating Gains

Whether gains are made in one’s own investment or the investments of others, the instinctive reaction is to acquire more of the winning investment. This reaction has been a poor choice in a large number of cases since investments seldom repeat performance.

The result is that investors “chase yesterday’s winners”. This is analogous to a horse racing strategy, in which you bet on horses that won the previous race!

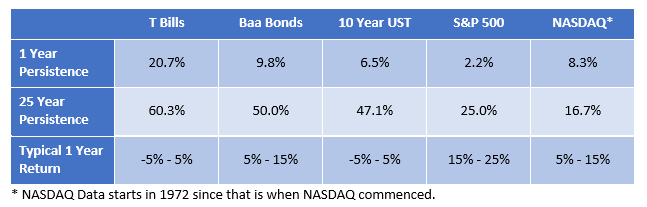

Historical data shows that the ability to repeat performance[1] differs for different investment classes and different time frames. For example, the most widely held equity investment, the S&P 500, repeated its annual performance on only two occasions in nearly 100 years. The odds of success are pathetically low for those who select these investments in the hope of repeating the performance of a good year. The odds do improve over time, up to one in four if the investment is based on a 25-year performance.

[1] An investment return is treated as being repeated when the subsequent period has a return that is + 10% of the previous period’s return. For example, a performance of 5% is repeated if the subsequent period’s performance is between 4.5%-5.5%.

Avoiding Losses

Abandoning an investment after underperformance is another natural reaction, which is very much as flawed as “chasing yesterday’s winners”. This could be described as “closing the barn door after the horses have escaped”!

Historical data shows that it is doubly unwise to abandon an investment due to underperformance since the most widely held equity investment repeats annual performance so rarely, twice in nearly 100 years. In addition, there is a 68% likelihood that this investment after suffering a loss will produce a gain the next year.

From an ERISA litigation standpoint, it is not imprudent for a fiduciary to maintain an underperforming fund in a plan line-up if the leading indicators of success of been evaluated and found to be favorable. See a list of leading indicators in Appendix A.

Combating Reality

In recognizing the harm that these reactions to gains and losses cause, regulators, the investment community and industry groups have adopted practices to mitigate the harm.

Regulations

Regulators have required that investors are made aware of the dangers of using past investment returns in the decisions regarding their actions. Unfortunately, these regulations make no distinction between classes of investments that are more likely to repeat performance and those that are less likely. By using this “one size fits all” approach the non-repeaters are combined with the repeaters.

The result is that repeating classes are treated with the same caution as non-repeaters. Non-repeaters are given credit for the possibility of repeating.

The Benchmark Shell Game

The investment community has introduced a concept that redefines success. Under this counterintuitive redefinition, success is earning or losing returns that match or exceed an average similar investment. Thus, the Benchmark was invented. Interestingly, the Benchmark concept does not put weight on whether the investor has made or lost money, only whether the investment is ahead or behind its peers. The result is that approximately half of investments are always winners, even if they are all losing money for investors.

The Benchmark concept has been highly successful in making investors actually believe that it is in their best interest to beat the Benchmark.

The Benchmark concept has also become the norm for investment manager compensation. Managers earn bonuses for beating the Benchmark, often with no incentive for making money or disincentive for losing money!

The result is that there are now hundreds of thousands of investment Benchmarks. These include an ever growing number of asset classes, time frames and other distinguishing characteristics. If there is no Benchmark that makes an investment look successful, then one is simply invented!

Benchmarking also prevents competition across asset classes, destroying the incentive to earn better returns. Instead of investors making the important decision of what asset class to use, the individual investment is compared only to others in the same class.

As flawed as the Benchmarking is, it has made its way into the legal and regulatory systems.

A Better Way

The investor’s need to know and prudent decision making can be enhanced by a measure of investment persistence. This measure can be applied to individual investments or to classes of investments and relies on the probability of changing returns in the future. Persistence is combined with an evaluation of the factors that have been leading indicators of investment returns and investment losses.

Ending demonstrably imprudent investment practices is the second most important course of action. These practices include ending reliance on past returns to make investment decisions and the use of Benchmarks to obfuscate and reward losses.

The primary indicators that should be evaluated are in this blog article. These are not the only factors and it is essential that additional factors are added when applicable and removed when they do not apply.

%20(1).png)

SUBMIT YOUR COMMENT